North Irokos, or Nirokos, three hundred thousand of them, are tall, darker than blue but not quite black, round-faced with tight curly hair. They had evolved noses on average 3 mm shorter than those of their Southern cousins, to protect them from the evil wind that blew from the South said the socio-molecular anthropologists. Nirokos are famous for their big mouths. If you had a big bum, stroppy spouse, spoiled sprogs for kids or halitosis they soon let you know. When Queen Elizabeth II visited North Roko, Prince Philip refused to come.

Nirokos are easy-going. ‘We live in the moment, our cousins live for the moment their day will come,’ said their beloved King Dela. ‘You only need to look over the waters to the African mainland, or down south to Sirokos,’ he said. ‘Jungles thick with holy shrines, churches, mosques, temples; shocking towns without running water or electricity.’ Yet no religious holiday, Christian or Buddhist, Juju or Jewish, came along without the Niroko joining in the juicy parts; the gospel songs, the feasts at the end of the Ramadan fasts; and they drank more beer than the most devoted disciples of Bacchus.

When the Chinese found Tantalum King Dela, afraid that a windfall would destroy his people’s way of life, sent a business delegation packing with typical Niroko words of one syllable. On their way back the Chinese stopped over to see Babubacka.

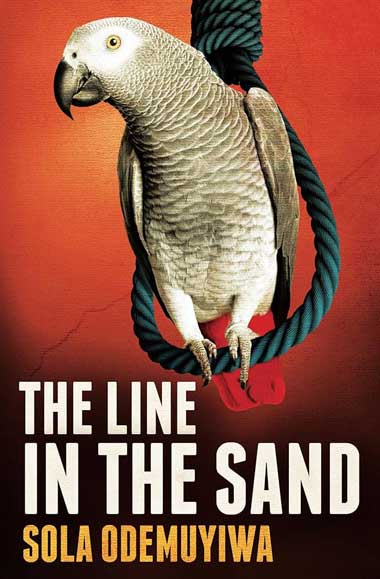

On a sultry Tuesday morning, with the world distracted by the attacks of terror on the USA by Saudi Arabian citizens, Babubacka and his Rokopats overran North Roko at 630 am on Wednesday the 10th of September 2001. They sent the King into exile and Archimedes II, his world famous African Grey parrot, died a few days later. Rokopat soldiers impounded the cars and beat up the house servant, Esau, who has not been heard of since, and marched Wale, Jane and Dele, Innocent, the parrot and two other families on to a dinghy and took them to a camp in South Roko where, after a month of wrangling over the level of bribe, the camp superintendent helped Wale to find the rooms to rent on Nigeria street, in one of the huts and shacks built out of mud, wooden slats, corrugated metal sheets, aluminium girders filched from motorway central reservations or sawn off telegraph poles, or, as Wale described them, ‘dwellings built from rubble by the rabble for the rabble.’